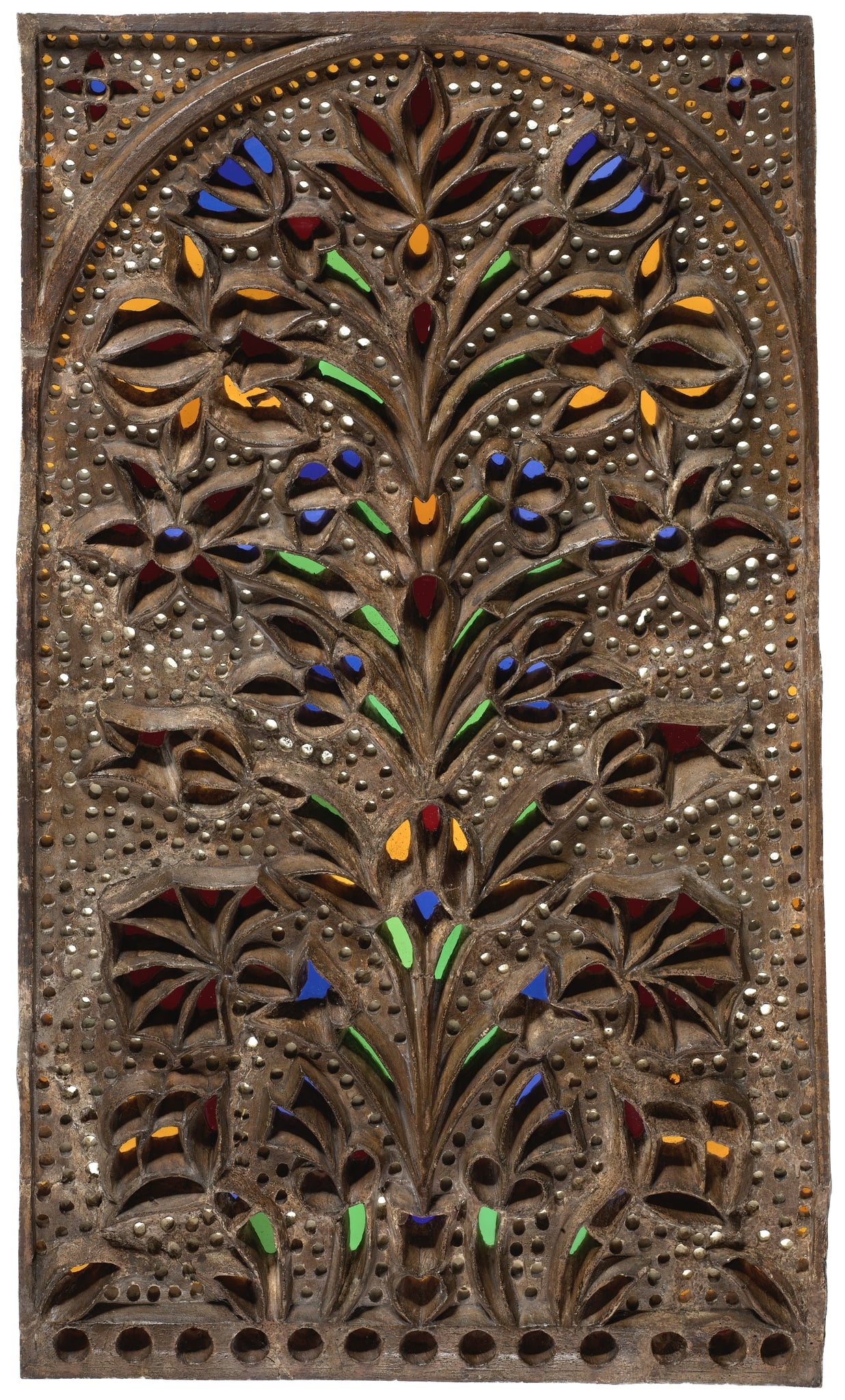

From a technical and iconographic point of view, this stucco and glass window corresponds to one of the standard types of qamariyya widespread in Egypt during the Ottoman period. Similar windows can be found in several of the collections studied (see for instance IG_7, IG_166, IG_178, IG_255, IG_356). The representation of flowers in a vase is a widespread motif in Islamic arts. It can also be found in numerous other media, such as ceramics, wood panelling, wall paintings, and textiles, over a long period of time, and in both sacred and profane contexts. Depending on the quality of the design, the type of flower cannot always be identified. Among the most sophisticated examples of stucco and glass windows with the vase motif are those in the apartments of the Crown Prince at the Topkapı Serail (early 17th century CE, date of the windows uncertain) and those in the Sultan’s Lodge (Hünkâr Kasrı) of the Yeni Cami (1661–1663 CE, date of the windows uncertain), both in Istanbul.

Stucco and glass windows with flowers in a vase also aroused the interest of Western artists and architects, as is attested by a significant number of book illustrations, sketches, and paintings (see for instance IG_43, IG_118, IG_149, IG_153, IG_437, IG_443, IG_461), as well as by the replicas of such windows installed in Arab-style interiors across Europe (IG_54–IG_59, IG_64, IG_431, IG_484–IG_487).

The window from the Louvre discussed here differs from most of the other examples, owing to the smaller size of the vase. The quality of the execution of the stucco lattice and the precise depiction of the flowers demonstrate remarkable skill and craftsmanship. The colours and material properties of the glass and the latticework – although heavily restored – suggest that the window dates to the late 19th century. This assumption is supported by the results of an analytical study of glass from two stucco and glass windows from the Louvre collection (OA 7466/7, OA 7466/25) conducted by a team from the Musée du Louvre (Fellinger et al., 2022).

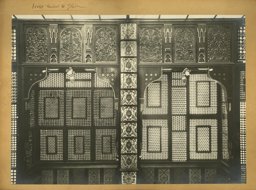

As to its provenance, the window is one of 39 qamariyyāt supposedly bought in Cairo by the architect Ambroise Baudry (1883–1906) for the French civil mining engineer and art collector Baron Alphonse Delort de Gléon (1843–1899) (Bailly et al., 2008, pp. 16–24). They adorned the Ottoman salon of Delort de Gléon’s hôtel particulier, purchased in 1883, at Rue de Vézelay 18 in Paris (Volait, 2005, pp. 131–134; Volait, 2009, pp. 99–104, 130–135). This is confirmed by several historical photographs preserved at the Département des Arts de l’Islam (DAI) of the Musée du Louvre, which show the windows inserted in the upper parts of wooden mashrabiyyāt (see Linked Objects and Images). The salon was designed by the baron himself in collaboration with the French architect Jules Bourgoin (1838–1908). The creation of orientalizing interiors, composed of original architectural elements and furnishings as well as replicas of the same, was a widespread practice among Western art collectors at the time (Giese, 2016; Volait, 2016; Giese, 2019).

Based on these photographs and the presumed date of the windows, one may assume that the windows were created especially for Delort de Gléon’s Arab-style interior and had never been part of a historical building in Cairo. The complete history of these windows however, including possibly multiple reuses and several restorations, is difficult to reconstruct. Based on the unpublished study by Bailly et al. (2008) and our own observations, it seems that most of the windows of this collection have been cut from their wooden frames. Extensive repairs to the stucco grille, as well as the partial or complete replacement of the thin plaster layer for embedding the pieces of glass at the backs of the panels, are proof of several restoration campaigns. It is likely that the light-brown (ochre-coloured) paint on the inside of the stucco grille is not original but was applied around 1922 in preparation for the display of the window in the exhibition rooms of the Louvre, with the intention of adapting the windows to their new surroundings (Bailly et al., 2008, pp. 16–24). The brown varnish applied on top of the paint is probably also the result of a restoration campaign, possibly before the Louvre exhibition in 1977, and may have been applied to match the colour of the wooden mashrabiyya in which the windows were displayed.

After the death of Delort de Gléon, the stucco and glass windows passed into the possession of his wife, Marie Augustine Angélina Delort de Gléon, who bequeathed them – as part of Delort de Gléon’s collection of Islamic art – to the Musée du Louvre in 1912 (Delort de Gléon, 1914).