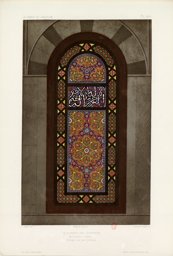

De Vogüé outlines how Sultan Suleiman Qanuni renovated the Dome of the Rock in the years following the Ottoman conquest of Jerusalem in 1517. He states that the window openings were fitted with stucco and glass windows and transcribes the inscription on the windows. This continuous inscription once ran from window to window and gave Sultan Suleiman’s name, as well as the date 935 AH / 1528–29 CE.

De Vogüé regrets that many of these windows in Islamic lands, which were already rather rare, have disappeared. He continues with a brief description of the technique and praises the effect of the soft, coloured light entering the building. Particular emphasis is laid on the oblique carving of the stucco panels, which result in the coloured light not only being directed into the room, but also colouring the stucco itself; this leads to a subdued light effect – ‘une pénombre lumineuse’ (de Vogüé, 1864, pp. 96–97).

With his publication, large colour illustrations of stucco and glass windows were published for the first time. Their size and their composition, divided into several parts, is typical for mosque windows. Such larger windows did not enter European collections. Occasionally, however, inscription panes were imported that may originally have been part of larger windows (see The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 93.26.10, IG_147; Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 1202-1883).

De Vogüé’s illustrations and the transcribed inscriptions are a valuable source for the study of the windows of the Dome of the Rock, which are now lost. A great restoration in 1291 AH / 1874 CE under Sultan Abdulaziz, as well as a number of subsequent interventions, led to the replacement of probably all the windows (Flood, 2000, p. 433). That the three windows are all of different forms indicates a high variety of window designs. There were originally almost certainly several other window types. At least one of the windows of the 10th century AH / 16th CE recorded by de Vogüé (IG_73) is no longer represented among the types now in situ. Flood points out that the stucco and glass windows were probably designed in an imperial scriptorium and executed on site, by craftsmen from Egypt or Syria (Flood, 2000, pp. 436, 441).

Émile Prisse d’Avennes had two of de Vogüé’s plates (IG_71, IG_72) in one of his portfolios (‘Dessins arabesques’ 1, Fonds Émile Prisse d’Avennes sur l’Égypte, Bibliothèque nationale de France). Julius Franz (in his Die Baukunst des Islam, 1887, see IG_66), Léon-Augustin Ottin (in Le Journal de la peinture sur verre, 1897, see IG_282), and Henri Saladin (in the Manuel d’art musulman, 1907, see IG_45) refer to de Vogüé’s book, because of the unique illustrations of the windows there and the description of the effect arising from the oblique carving of the stucco panels.