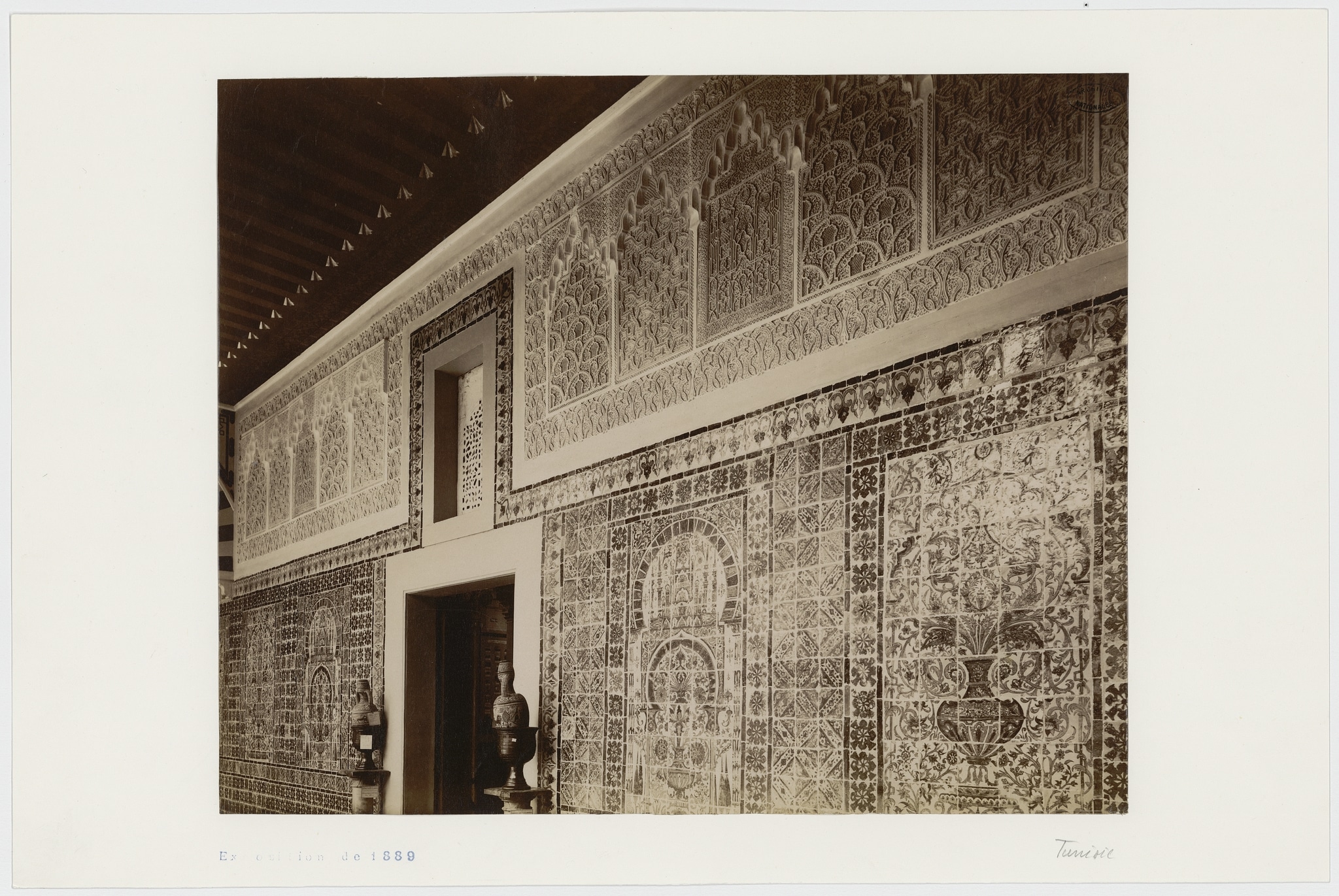

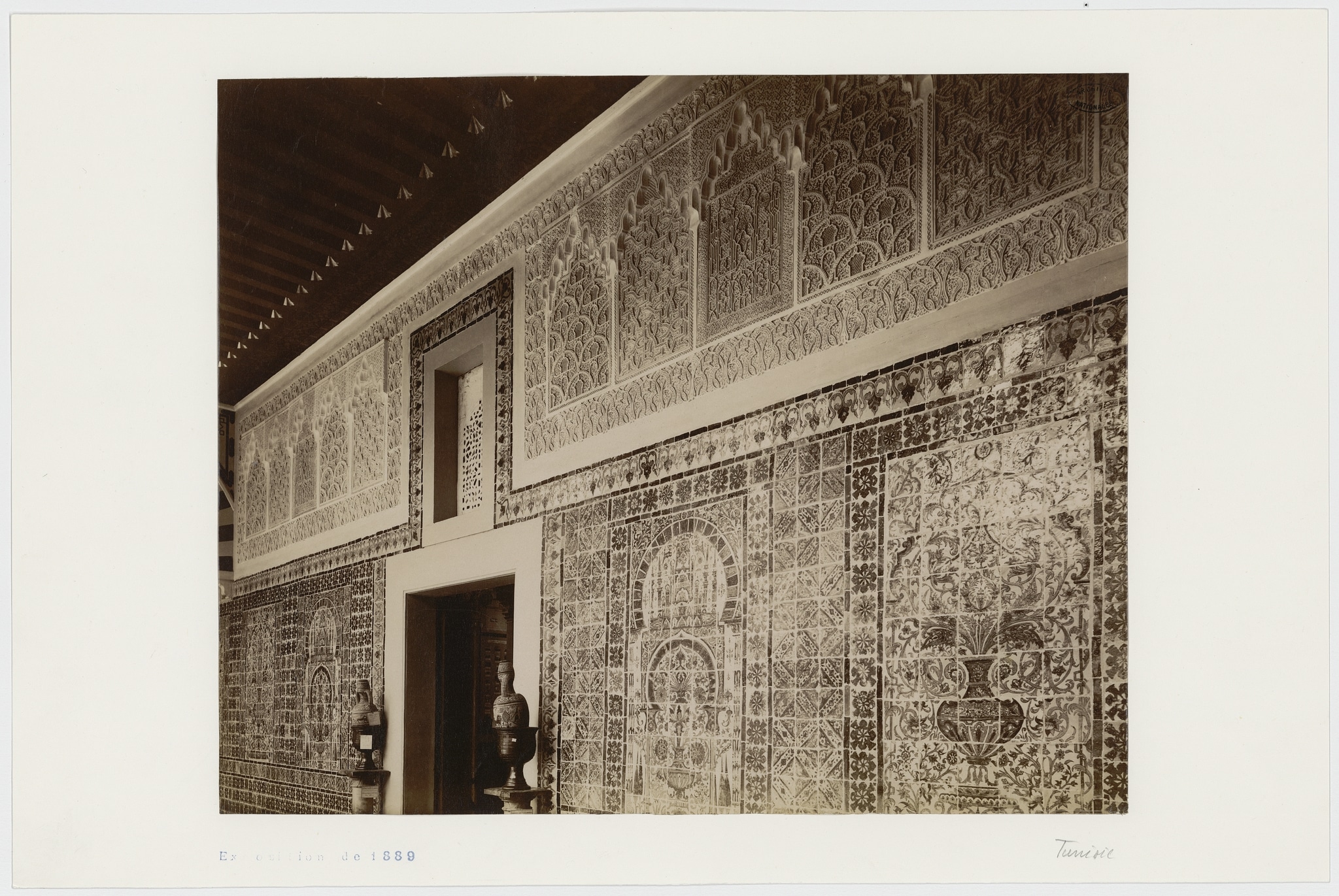

This photograph records the technique used for producing the stucco and glass windows of the Tunisian pavilion at the Exposition Universelle in 1889 in Paris. It can be seen that the small coloured pieces of glass were set in the wet stucco on the rear of the lattice, indicating that the stucco and glass windows were made using the traditional technique practised in Tunisia.

This observation is confirmed by descriptions in exhibition reviews as well as by a written account of the Tunisian pavilion’s architect Henri Saladin. For instance, in the exhibition report La Tunisie à l’Exposition de 1890, Pauline Salvari describes the technique for making so-called chemsahs (shamsiyyāt) as follows. The artist usually works on freshly cast plaster, on which he draws the pattern, which he then cuts out with a sharp tool like a chisel. The openings of the plaster lattice are then sealed with coloured glass. She points out further that this is impressive work that takes a lot of patience. (Salvari, 1890, p. 96).

Louis Brès described the production of these windows in even more detail in a journal article on the 1889 Exposition Universelle, ‘L’art dans nos colonies et pays de protections’. The design of the windows is based on pattern drawings on paper, collections of which were handed down by Tunisian workers from generation to generation. These designs are applied to plain, hardened plaster plates set in a wooden frame, and then the parts that should be exposed are carved out in the workshop, creating a stucco lattice. Finally, pieces of coloured glass are glued to the back of the plate. The stucco is carved obliquely so that, once installed in the building, the viewer below can not only see the window itself, but also the colours of the glass reflected by the lattice (Brès, 1889, p. 201).

According to Brès, the information on the windows’ production technique was given to him by the pavilion’s architect Henri Saladin, who mentions in his publication Tunis et Kairouan that he commissioned Tunisian craftsmen to make the stucco and glass windows of the 1889 Tunisian pavilion (Saladin, 1908, p.56). However, rather than explaining the production technique, Saladin focuses on the stucco and glass window’s stylistic development in the general context of architectural decoration in Tunis, the exchange of craftsmen, the preservation of heritage, and the contemporary status of traditional craftsmanship (IG_248).

The rear of the window visible in this photograph, together with a photograph of a stucco window reproduced in Saladin’s Tunis et Kairouan (IG_249), which may illustrate a window made for the Exposition Universelle of 1889, support the assumption that windows of the same typology as seen in earlier Tunisian representations at world’s fairs were shown at later fairs. Stucco and glass windows with geometric patterns based on stars under arches and non-perforated spandrels were displayed at the Great Exhibition in London in 1851 (IG_410), at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1867 (IG_271, IG_273), as well as at the International Colonial Exhibition in Amsterdam in 1883 (Victoria and Albert Museum, 1277-1883). In addition to the window from the Amsterdam Colonial Exhibition preserved at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, several windows of this typology that entered the collection of the Orientalische Museum (now in the MAK Vienna) in the 19th century (IG_362, IG_363, IG_364, IG_365, IG_366, IG_367, IG_368) demonstrate the availability of this type of stucco and glass window in 19th-century Europe.