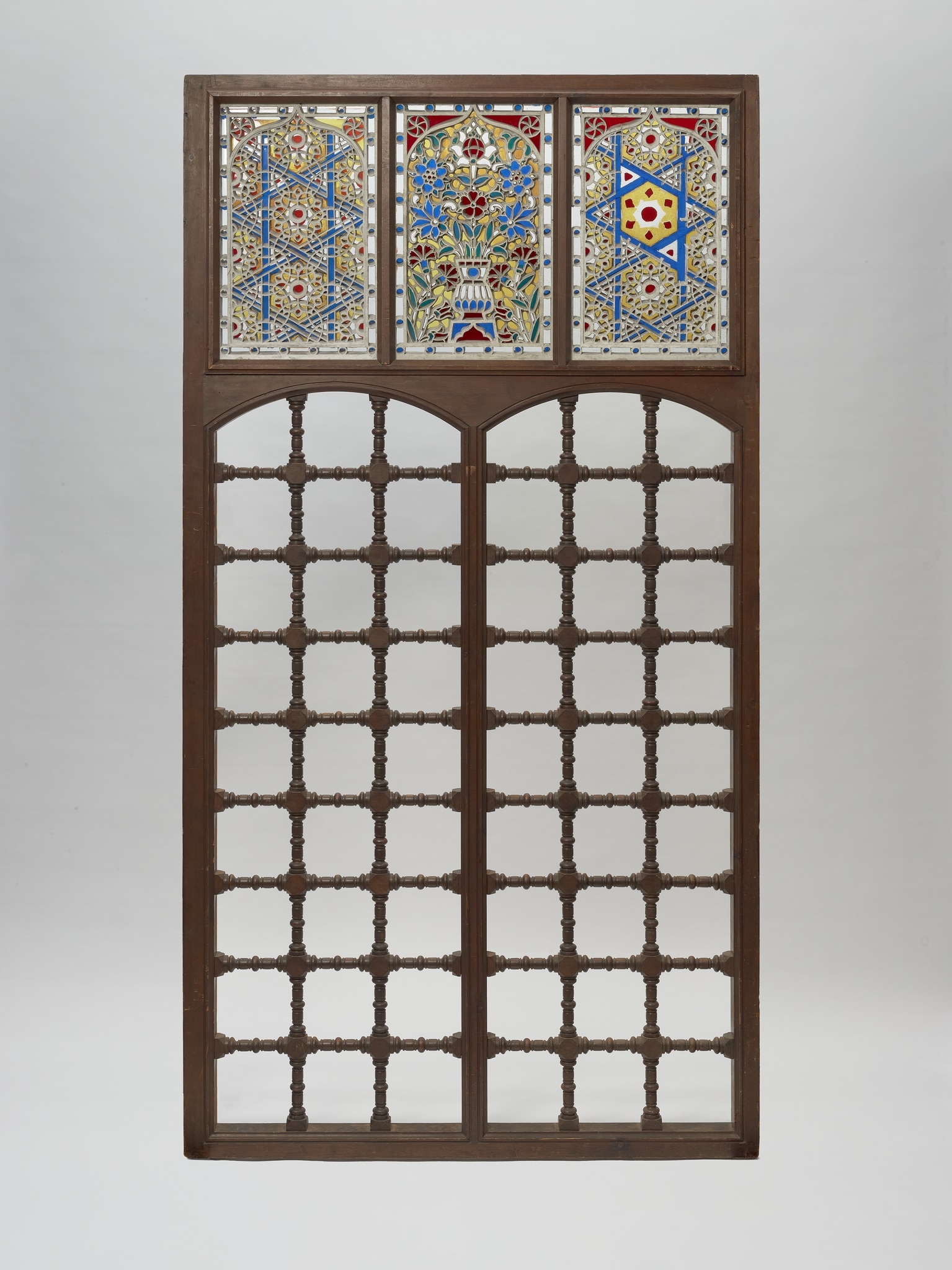

This wooden mashrabiyya with the three replica window placed in its upper section is part of the Arab Room (Arabisches Zimmer) designed by the Czech architects František Schmoranz (1845–1892) and Johann Machytka (1844–1887) for the k.k. Österreichisches Museum für Kunst und Industrie. The museum, now known as the MAK – Museum für angewandte Kunst, was founded in 1863 by the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph I (1830–1916).

The Arab Room project started with the donation of several wooden furnishings (doors and wall cabinets) from a group of Egyptian buildings designed by Schmoranz for the Vienna world’s fair of 1873 (see for instance IG_227, IG_457, IG_458) to the k.k. Österreichisches Museum für Kunst und Industrie (MAK Archives, AZ 1881-190, see also Lauser, 1883, pp. 15–16). In order to present the pieces as part of the permanent exhibition, the museum followed the widespread trend of creating rooms in specific styles composed of original furnishings and contemporary replicas made by local artisans. Comparable examples of such rooms dating to the late 19th and early 20th centuries can be found across Europe, for instance in the Maison Loti in Rochefort (IG_426–431), in Leighton House in London (IG_48–IG_59, IG_91), and in the fumoir arabe of Henri Moser Charlottenfels in Bern (IG_64).

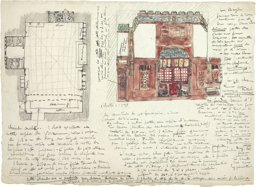

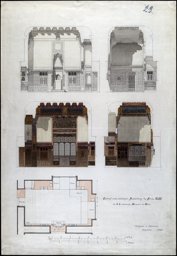

According to a preliminary design for the Arab Room by Schmoranz and Machytka dating from 1881, the planning of the Arab-style interior had already begun in 1881 (see Linked objects and images). Both architects had first-hand knowledge of the Islamic architecture of Egypt, and more specifically Cairene domestic architecture, from which they drew the models for the Arab Room. The latter represents a simplified version of a qāʿa, the traditional reception room of Ottoman houses in Egypt. Originally located at first-floor level towards the Ringstrasse, the Arab Room was inaugurated on 1 May 1883 and remained at its original location until 1931, when it was dismantled and moved into storage. Today, the Arab Room is only partially preserved. However, the preliminary design by the architects mentioned above, together with a partial view of the room published in 1883 (Lauser, 1883, p. 17), two historical photographs by Josef Löwy taken before 1897 (MAK, KI 7266–1, KI 7266–2), as well as five drawings by the Swiss architect Le Corbusier (Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, 1887–1965), executed during his stay in Vienna from November 1907 until mid-March 1908 (Paris, Fondation Le Corbusier, DE_2055, DE_2081, DE_2082, DE_2116, DE_2117, see Sekler 2000), give us at least some idea of the original setting (see Linked objects and images).

Three of the original six stucco and glass windows installed in the upper part of two custom-made wooden mashrabiyyāt (MAK, H 3358-3 (windows lost today), H 3358-4) have been preserved. They are reminiscent of traditional qamariyyāt in terms of their position in the upper part of the window opening and the symmetrical arrangement of the windows, with the central window being flanked by two identical windows (for comparison see for instance IG_118, IG_119, IG_449).

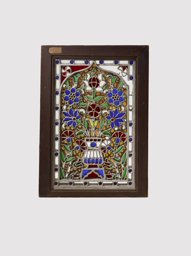

The central panel (2) corresponds iconographically to one of the standard types of qamariyya widespread in Egypt during the Ottoman period. Comparable windows can be found in several of the collections studied (see for instance IG_7, IG_166, IG_178, IG_255, IG_356). The flowers in this replica are depicted in a more naturalistic way than those of Islamic stucco and glass windows from Egypt. It is therefore likely that the window was designed by a Western architect or artist. The motif of flowers in a vase is illustrated in numerous 19th- and early 20th-century publications. The illustrations were well known across Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They served as a source of inspiration for numerous architects and were probably also used as models for new windows. The designer of the stucco and glass window in the collection of the MAK (OR 3607, see IG_361), which was the direct model of the flowers in a vase replica discussed here, may have drawn his inspiration from an illustration by Émile Prisse d’Avennes (1807–1879); see IG_43. In contrast to the replica, the ‘model’ was made using the traditional Islamic technique of embedding coloured pieces of glass in a thin layer of plaster on the reverse side of the latticework. The naturalistic rendering of the flowers, however, clearly identify the designer as being Western.

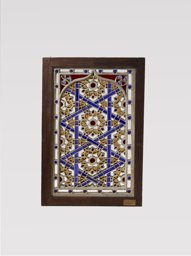

The design of the side panels (1) and (3) differs significantly from Islamic examples, despite the symmetrical layout of the individual elements (circles, flowers, bands). A direct model for the two windows may have been a stucco and glass window that originally formed part of the collection of the Orientalisches Museum (from 1886 the k.k. Österreichisches Handelsmuseum) in Vienna (MAK, OR 3606, IG_360). As the above mentioned window (IG_361), this prototype was also executed according the Islamic manufacturing technique. It is likely that these windows too were designed by a Western architect or artist and subsequently transferred, together with other stucco and glass windows, to the k.k. Österreichisches Museum für Kunst und Industrie in 1907 (Wieninger, 2012).

The replicas in Moser’s fumoir arabe (IG_64), the Selamlik at Oberhofen Castle (IG_322–IG_328), were made in the Western stained-glass technique. Schmoranz and Machytka, however, opted for an unusual and much simpler technique by placing painted panes of glass behind the stucco lattice. In a newspaper article published on 3 May 1883, the Tiroler Glasmalerei Gesellschaft is mentioned among other Austrian workshops involved in the realization of the Arab Room (Anon. 1883). According to Sekler, the Tiroler Glasmalerei und Kathedral Glashütte are also listed in the final invoice dated 7 July 1883 (Sekler, 2000, pp. 264–265). Even though the invoice mentioned could not be located in the MAK archives, it is very likely that the Tiroler Glasmalerei und Mosaik-Anstalt founded in 1861 in Innsbruck was in charge of etching the red flashed glass and painting it with silver stain and coloured enamels.

As intended by the k.k. Österreichisches Museum für Kunst und Industrie, the Arab Room of the MAK and its windows quickly became reference works for local architects, artisans and patrons (Anon. 1883, see also Lauser, 1883, p. 16), as attested by another Viennese interior (see IG_371–IG_375), executed in 1901 for the Austrian entrepreneur Anton Johann Kainz-Bindl (1879–1957).